Sharpest and Strongest Teeth in Nature

Posed as a question, it would seem relatively easy to answer.

Instantly our mind moves to shark!lion!pihrana! before immediately running away because they are three scary thoughts. Apparently though, a shark will pursue us only if it thinks we are a seal. Yet no research team is working on how to emblazon Not A SEAL in shark language on wetsuits to avoid what are no longer “shark attacks” but “shark events”.

The last one of those I saw was Sharknado.

It’s not just a matter of having the biggest mouth to have the sharpest teeth. The bowhead whale might have the largest mouth of any animal, but it doesn’t bite. Blue whales are the biggest creatures on earth and they don’t have the biggest bite because they simply have no teeth.

A bite is delivered by teeth and muscle, so it’s not so easy to find the biggest bite on the planet that doesn’t have a CEO or a foundation.

It’s a two-part question anyway: it doesn’t always follow that the sharpest are the strongest.

Two hundred million years ago, the world’s most razor fangs came in a bite-sized package just five centimetres long. Conodonts (from the Greek konos, “cone,” and odont, “tooth”) were eel-like creatures with teeth that while small, were incredibly sharp; the sharpest ever discovered. The tips measure just 2 micrometres across – less than an eighth of the width of a human hair.

But sharp is not always a good: sharpness is demonstrably vulnerable to breakage. How conodonts like went about eating required computer models to find how it was they functioned without being crushed to chalk.

Turns out these chompers didn’t chomp.

Paleobiologists found that the food processing mechanism of the conodont wasn’t based on muscular force. Instead, extremely concentrated, minuscule forces turned the usual up-and-down bite action by 90 degrees and sliced from left to right: trapping first at the back, rocking, and separating again.

Carcharodon megalodon was a whopping 20-metre shark, extinct for the last 2.6 million years with an estimated bite to be an enough to crush a small car. If you wanted a curious tattoo there’s some (I guess) Newtonian number for that: 108,514-182,201N.

Historical dentistry such as amalgam is a non sequitur to add for good measure.

So technically the sharpest teeth belong to theprehistoric and really can’t count, so the guernsey goes to the common garden snail that would surely take a bow only it can’t.

Firstly because clearly, it can’t; and secondly because these thousands of teeth, capable of withstanding the same amount of pressure it takes to turn carbon into a diamond, scrape, not gnash, so it cannot be said that they bite. It certainly has the most teeth though – about 140 000 or something that only a dentist dare dream.

3D element analysis has revolutionised predictions and dissections of bite force. Just because an animal can hypothetically generate a particular force doesn’t mean it does. FEA allows overall mechanical behaviour as a reaction force that can pinpoint stress and strain throughout the skull and jaws.

The Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences claims orca as the largest living creature to use teeth for catching and tearing. With around 50 conical ones, from seals to grey whale calves, prey is ripped apart. Nature is cruel but naturopathy is kind; it’s the reason no orca naturopaths are ever sighted choreographing sophisticated coordinated attacks. Maybe the size and demolition of the kill may not necessarily be comparable to a lone predator.

In which case you can’t go past the great white shark while praying it goes right past you. 300 continuously replaced, blade-like teeth give it one of the most feared bites on earth – which really happens in water.

Unless it’s Sharknado.

Surely bigger bite pressure makes even relatively blunt teeth behave more axe-like than rubber mallet.

Brown bears have to fit somewhere into this landscape. There’s skull-crushin’ power in them thar jaws.

If you had to run into water to escape a brown bear at least you’re not going to come across a saltwater crocodile. Unless it’s in one of those stupid dreams where you’re just being chased all the time and nobody has any cake.

Florida State University studies show that it’s not the teeth or long jaws that give crocs the bite on big bites – it’s their ferocious snap. Their jaw-closing muscles has positive allometry – the truly perfect relationship of body size to shape, anatomy, physiology and behaviour. As crocs grow, jaw muscles grow relatively faster than one might expect.

Ah so many gnasher contenders; not a short a list, and yet it is when you think of how many critters there are on the planet.

Or would be if we stopped wiping them out.

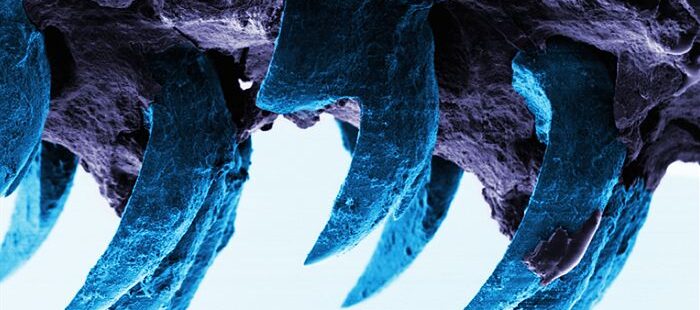

The assumption that sharpest teeth are the strongest has already been cut down without even mentioning the limpet. Limpet teeth are the strongest natural material on earth: six times stronger than spider silk, and equal to ultra-resistant carbon fibre.

It’s why you can’t prise a feeding limpet from a rock with a crow bar. Which should be a meme for tiresome guests. It has the strength of dental bonding that would stratosphere the income of a dental technician.

Limpet teeth are both stretchy and strong. They contain millions of aligned nanofibres, made from the mineral goethite, which are embedded in a softer shell of chitin – a biopolymer that functions as scaffolding. Teeth can stretch to four times their original length without losing elasticity or breaking. Being able to mimic the biological structure could help engineers build better cars, boats and aircraft.

“Look! Up in the sky! It’s a bird! It’s a plane… it’s a flying limpet..?”

Just what we need. More stuff doing stuff moving stuff consuming stuff.

Humans certainly don’t have the sharpest or strongest teeth in comparison to many animals. Often we don’t have the sharpest brain.

Maybe it is the blunt and dull that has inherited the Earth.